PC John Zollner of the City of London Police was probably not an easy man to deal with. Undoubtedly principled and brave – he was an “Old Contemptible” – the Commissioner of the time, Sir William Nott-Bower described him as a “man of considerable intelligence”, but also one who could be “offensive and provocative”. He also had the habit, which Nott-Bower found extremely annoying, of referring to his fellow constables as “brothers” and “comrades”.

John was born Johann Heinrich Freidrich Zollner in March 1885. His mother and father, Catharine and August, were German immigrants to London’s East End where they had settled amongst many of their fellow countrymen and where August carried on his trade as one of the area’s numerous sugar-bakers. John though, chose a different path. By the age of 15 he is working aboard the “Harlech Castle”, a vessel used to ferry troops to and from England during the South African Boer War. A switch to a career on dry land follows when he joins the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards in 1903.

Three years in the Army and another career change. 1906 and John is now a City of London police officer working on from Bishopsgate Police Station. He marries a couple of years later and the 1911 census finds him living in Hanover Buildings, Tooley Street with his wife, Amelia, and two children, John Henry and Dora. While Dora was to live to adulthood, John Henry died within a few months of the census, aged 2. John’s second son Frederick, born in 1916, was also only to live to just before his 2nd birthday.

John’s early decision to become a Guardsman was to cast a long shadow over his life. Prior service in the Army meant he was placed on the Army’s Reserve list and so liable to immediate call up when war was declared on Germany in 1914. On 5th August that year, he once again found himself a Grenadier Guardsman heading off to France.

John though, does not forget his former colleagues and in February 1915 he writes to them, recounting a little of his life at the front. After describing the trenches as being like rivers, with water varying from knee to chest height, he goes on:

“A certain portion of the German line had a mark on the corner of our trenches where my section and I were. In the morning, they attacked, but our rapid fire smashed them up and so I suppose they thought they would try and snipe us off, but it did not come off. They however, knocked the foresight off my rifle. When I got fixed up with another they knocked my bayonet off. But it was no good – they could not get the man behind, and that, comrades, is the main thing”.

The Germans never did get their man and John Zollner continued to dodge their bullets until February 1916 when, suffering from rheumatism and trench nephritis, he was medically discharged from the forces. His war service entitled him to the three WWI campaign medals, the 1914 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal.

Rejoining the City of London Police, John returned to a City rather different from the one he had left. He now worked alongside members of the War Reserve and Special Constabulary as well as former colleagues, undertaking not just the usual police duties, but a raft of additional duties war had brought: enforcing the blackout, alien registration, patrolling significant points, and dealing with aerial bombardment, first from Zeppelins, and then from German Gotha airplanes. Hours were long, leave was scarce and pay was way behind inflation – experienced officers’ wages were less than the average rate for unskilled labourers. There was also no formal way officers could seek redress or make their grievances heard. Discontent was brewing.

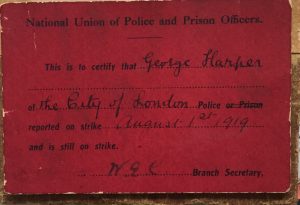

The only previous blemish on John’s service records – both in the police and Army – had been in 1912 when he had been found drunk on his beat in Mincing Lane. However, at some stage he becomes involved with the National Union of Police and Prisoner Officers (NUPPO), founded in 1913 by the militant former Metropolitan Police Inspector John Syme. Nott-Bower regarded those belonging to the Union as “disaffected agitators”. By 1918, Zollner is the NUPPO official in the City of London Police, an Executive Officer of the Union and one of its most active members.

It was also in 1918 that, following demands for the reinstatement of PC Tommy Thiel of the Metropolitan Police who had been sacked for his NUPPO membership, and for better pay, thousands of officers left their beats and went on strike. Over 6000 London officers withdrew their labour. On 31st August 1918 there was a mass march to Whitehall. It was joined by five hundred men of the City Police who assembled in front of the Royal Exchange in the City of London. They were instructed to stand firm, but to remember that, as members of the City of London Police, they were also gentlemen. At Whitehall the executive of NUPPO negotiated directly with the Prime Minister, Lloyd George. The result – Tommy Thiel was re-instated, wages were increased and the police returned to work, having won their victory. This gave the executive of NUPPO a mistaken confidence in their ability to influence, and even coerce, the Government.

Zollner continued his work in support of the Union, leading on the in-force negotiations with Nott-Bower on the establishment of Representative Committees, created to raise any welfare matters or grievances with senior officers on behalf of the men. The Representative Committee’s later suggestions included that “all future promotions in the Police (should) be made by competitive examination only” (Nott-Bower contended this would eliminate “any question of personal fitness or qualifications for higher rank”), and that the Corporation should build a “garden city” outside London for occupation by the police.

Nott-Bower later recounted that Zollner had started one of their meetings by saying: “The strike was not a question of money, it was justice they wanted, and brotherhood among the men. It was caused by the dismissal of Thiel, and there were six hundred members of the City Police who were members of the Union and insisted on its full recognition”. And it was recognition of the Union that prompted the second call to strike action issued by NUPPO. Press reports state that the first police officer to walk out in London – on 31st July 1919 – was PC John Zollner of the City of London Police.

- Tommy Thiel addressing striking officers, Tower Hill, 2nd August 1919

- Crowd of striking police officers, Tower Hill, August 1919

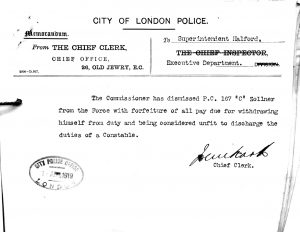

However, support for this second strike is generally poor. Twenty four hours later, Zollner is still the only absentee from his force . He was convinced though that he would be joined by others – he announced that his “comrades would wait until 2 o’clock and when they had got the money for the women and kiddies they would come out”. Indeed, after receiving their pay and holiday bonus, some comrades did join him – 57 in total – all were sacked and despite inquiries rumbling on into what senior police officers called a “mutiny”, none were ever reinstated.

- NUPPO Membership Card for PC George Harper of the City of London Police

- Zollner’s dismissal

Several of those involved in NUPPO went on to become involved in the labour and socialist movements. Tommy Thiel, and a number of other strikers, joined the Communist Party. Another later became the Labour Mayor of Hackney.

And what of John Zollner? Well, he set himself up as a gentleman’s tailor in Cumming Street near King’s Cross and seems to have done pretty well for himself. 1920 sees him writing to his old adversary, Sir William Nott-Bower asking if his ban from entering any City of London Police station could be lifted so he could return, visit old friends and perhaps pick up some new customers? The answer was a resounding no. And so John, who had lived through some of the most turbulent times experienced in England and in the police service, quietly carries on with his life and work, living just long enough to see the start of a second World War. He dies in early 1941, aged just 55 years.